For many of us, “Self-Mastery” may be a vague or unfamiliar term. I use it to describe my style of life coaching and it is part of my my website and business names. I thought it might be helpful to explain what I mean when I use this term. A typical dictionary might define “self-mastery” as “self-control” or “the ability to control one’s own desires or impulses.” Often, self-mastery is described as a function of will-power, as in mind-over-matter and that kind of thing. I will share a different understanding: that Self-Mastery is not primarily based on exercising will power to control yourself and your impulses. Read on to learn what I believe it is based on.

Let’s start at the broad level and drill down from there. I describe Self-Mastery as a process in which we humans can evolve and develop as adults, generating more clarity, self-compassion, and more complexity and nuance in how we view ourselves and our world. Rather than a permanent state that one attains, I describe it as something that must be practiced in an on-going effort (I’ll explain why below). This is why I refer to this work as the Practice of Self-Mastery. Self-Mastery is also an evolving experience of increasing freedom to choose our inner experiences (thoughts, beliefs, emotions, moods, and interpretations) and the actions our inner experiences lead to, which in turn yield changes in how our life feels and looks to us. Most of us, given greater freedom of choice, will opt for greater happiness, love and peace of mind, and less of the stresses and struggles we’ve habitually been engaged in.

If this self-mastery thing is not about controlling oneself through exerting will power, then how does it work? To answer that we will first take a brief tour through the origin and nature of the “desires and impulses” mentioned in the dictionary definition above.

The human organism is an astoundingly complex and miraculous living system that has evolved and prospered over millions of years. That evolutionary process has heavily favored survival of the human species, rather than, for example, the inner happiness or peace of mind of the individual human. Consequently, our bodies and our brains are built first and foremost to ensure species survival, and secondarily for experiences like individual inner happiness and peace of mind. This is why our bodies and minds can appear to be working against our inner peace and happiness. This is also why Self-Mastery is an on-going practice—the mind and body keep on defaulting towards survival, and we must consciously counter-balance that tendency in order to experience greater happiness and inner peace.

One of the systems in the human organism that prioritizes our survival is built into the structure of our brain. It is a system that prioritizes remembering painful, overwhelming or threatening experiences, and triggering strong emotional and physical reactions to new events that appear to be like those stored memories of painful or threatening experiences. It does this to help us avoid repeating past experiences that were perceived as threatening in some way. It is called the Limbic System and it is associated with the deeper, more primitive part of our brain. In order to prioritize our survival, the limbic system reacts with lightning speed to current experiences when there is an element similar to a remembered past threat or painful experience, either from our recent or distant past. This system is so fast, that the thinking parts of the brain are left behind while the limbic system blasts into a full sprint. The body’s autonomic nervous system kicks into alarm mode and prepares the body to freeze, fight or flee, by releasing hormones into our bloodstream. Once those hormones are in our system, we feel as though the threat is real, even if it isn’t. This feeling that we are under threat in turn causes us to think and act in ways that are consistent with that feeling, and now the experience of threat is reinforced, and feels intensely real. That is all part of our biology.

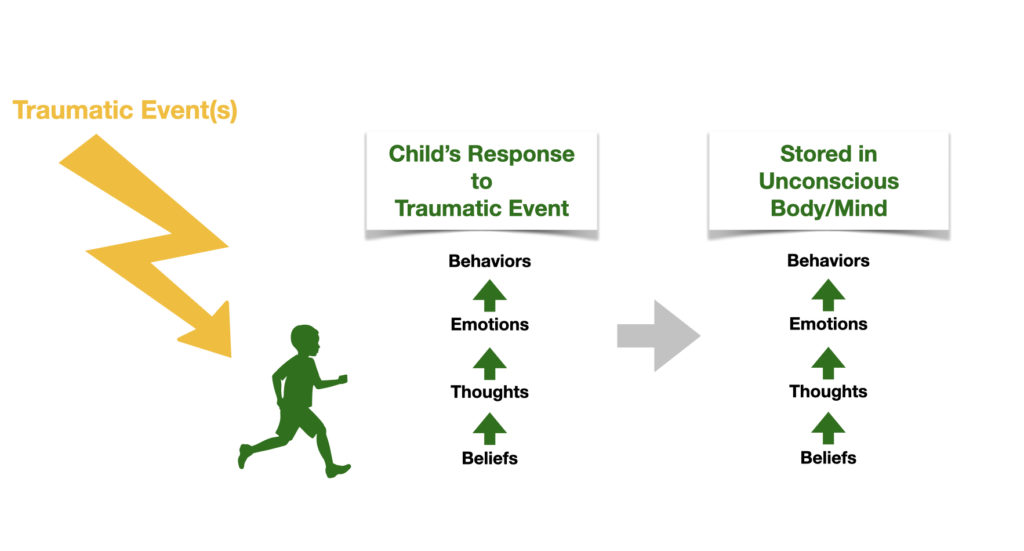

Where this gets really interesting is how these past memories of threat or pain are stored and organized in our mind as part of a point of view (or “sub-personality” or “part”). These elements of our mind each includes a set of emotions, assumptions, beliefs, thoughts and actions that linked and related to each other. In other words, together they form a way of understanding and responding to that past experience of pain or threat. In fact, these usually are the actual emotions, assumptions, beliefs, thoughts, strategies and actions that the person responded with when they originally experienced that past pain or threat. Since many of these points of view come from childhood experiences, I’ve illustrated it this way in the graphic below. However, please understand that these points of view can also come from painful, overwhelming, threatening or dangerous experiences from adulthood.

There are several challenges for us in the way this system works. First is that this part of the brain usually cannot distinguish between a real physical threat to survival, a symbolic threat, or something that simply has one or more characteristics similar to a past threat memory. Second, and even more challenging, if the painful or threatening event occurred in childhood, the point of view stored with the painful memory is that of a small child that experienced this painful or threatening event. In those cases, that means that our brain’s instantaneous response to the perception that this painful experience could happen again in the present leads to responses that often come from the point of view of a distressed child, rather than from an experienced and well-resourced adult. This is one of the weaknesses of our limbic system: when we are confronted with a possible threat, we lose connection with the reasoning part of the brain, from which we access our accumulated learning and wisdom, and instead our reactions and actions are guided by the point of view of a distressed child. See illustration below.

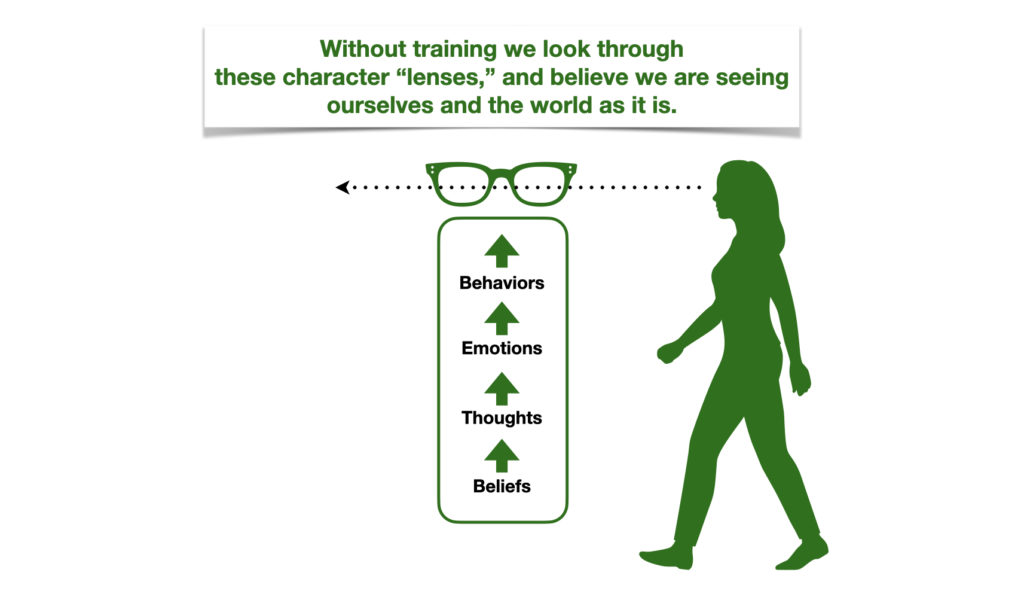

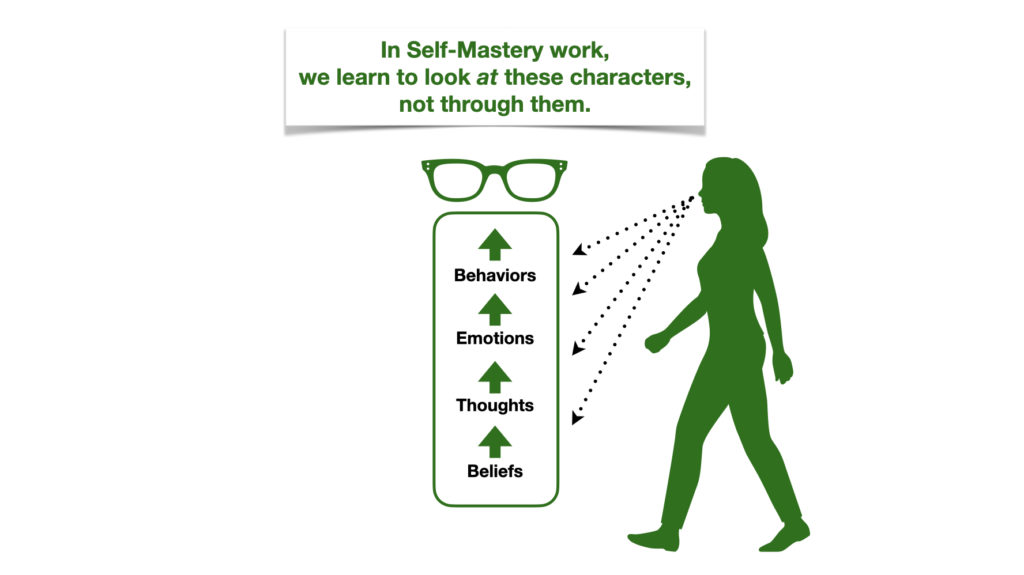

As crazy as this might sound if you haven’t heard it before, this predicament is also where great potential for the practice of self-mastery and its benefits are found. These points of view that are stored in our brain with past distressing memories can be thought of as parts of us, or characters, that is, as living entities within our mind and body. We can observe these parts, or sub-personalities as some call them. We can become aware of their emotions, thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors as distinct from the rest of our inner experience. The way in which we pay attention to these characters and the manner in which we relate to them is at the heart of the practice of self-mastery.

Let me give you an example from my own experience. When I was about 10 years old, my mother convinced me to take piano lessons with a teacher who lived around the corner from us. The piano teacher’s son was a neighborhood bully. He was older and much bigger and stronger than me. When I would go for my lessons, he would silently taunt me and disrupt my lesson in ways that his mother could not see. This was very scary and stressful for me at the time. When he also started harassing me on the way home from school, my distress rose to a high level. Before long, I refused to continue the lessons, but the memories and the distress were already stored deep in my brain. Many years later, I learned to play the guitar and eventually began to write and perform my own songs in public. I often thought about writing songs using the piano as a way to expand my repertoire, but something in me resisted taking any action towards further learning the piano. I didn’t know why, but I had a strong emotional aversion to learning the piano. Later on when I learned how to give my attention to this aversion in an open, curious and compassionate way, the memories that I had forgotten came back to me. I felt compassion for that boy who had to figure out how to contend with the bullying from the teacher’s son in an era when bullying was neither understood, addressed or talked about. The emotional response that drove my decision to quit piano lessons when I was 10 years old was also what was driving me now as an adult musician. I became very clear that it was not the adult Neil that had the aversion to learning to play the piano, but rather the 10 year-old me living in my mind. Once I learned to be aware of and to relate to and understand that 10 year-old, not as a concept, but as a real, living presence in my mind, I regained my freedom to make new choices about how I pursued my music writing.

The Practice of Self-Mastery

As I said earlier, self-mastery as I experience it and as I teach it, is both an on-going practice as well as the resulting changes in experience resulting from that practice. What are we practicing? The heart of the practice is learning to use our attention and awareness in new ways. We practice recognizing where our attention is, and developing the capability to intentionally move it to other aspects of our experience. Some of the aspects of our experience that we practice paying attention to in the self-mastery work are our emotions, our body sensations, our beliefs, and our habits of behavior and emotions. Each of these areas of our experience hold great potential for enabling transformation through the practice of self-mastery.

First let’s talk about your attention and awareness. These are two aspects of your consciousness. Attention is about what you focus your awareness on. Most of us don’t realize that we have unconscious habits of attention. We routinely pay attention to some aspects of our experience and ignore others. In Self-Mastery practice, we learn to become aware of what we typically pay attention to, that is, noticing the patterns of our attention.

Awareness is the process through which our mind receives all the inputs our human organisms are capable of receiving. Awareness is always there receiving whatever inputs are there, even if we are not consciously aware that this is occurring. In Self-Mastery, we practice being conscious of both that we are aware in the moment, and what we are aware of in that moment.

Practicing these skills of attention and awareness allows us to build our capacity to see and connect to the emotions, thoughts, body sensations and behaviors that are presented to us by these inner characters’ points of view inside our mind (as described above).

Through developing these awareness and attention skills, we can now pay attention to the details of the point of view that we are in at any given time. We can become aware of the mood, emotions, thoughts, beliefs and behaviors that are part of that point of view. And we can become aware that we are seeing and feeling a point of view within our mind. That awareness allows us to cultivate a “witness” point of view, from which we can objectively see and feel the perspectives of the characters that live inside our minds. Said another way, we practice shifting our point of view from looking through these inner characters’ points of view (collections of related moods, emotions, thoughts, beliefs and behaviors) to looking at their points of view.

This ability to be in outside of the character’s point of view, while able to see and relate to that character, enables a powerfully healing internal relationship. We can bring greater clarity, openness, acceptance and the compassion of our authentic adult self to these parts of our mind only when we are consciously aware of and feeling them, instead of lost inside the character’s point of view without realizing it. In the latter experience is where many of us frequently find ourselves before engaging in the practice of self-mastery. The practice of self-mastery builds in us, through on-going practice, the skill and capacity to make this shift in our point of view, from being identified with the inner characters point of view, to seeing that what we are experiencing is the point of view of an inner character. From this new, larger, and more wise and accepting point of view, we are able to make choices that support the process of healing and integrating these characters (or parts) into a more cohesive, happier and more peaceful sense of self. This is why I describe Self-Mastery as a practice of mastering your point of view.

In future posts on the Self-Mastery Blog, I will delve more into the details of these inner characters or parts, and how to cultivate a conscious relationship to them that will support healing and integration.

Thank you for reading. If you found this helpful, please share a link to this post with people around you that you think would be interested. You may be tempted to share this with someone you think desperately needs to read this, and, if so, I invite you to consider whether that need is in them, or in you.

Be well!